Chapter 2 - It took a particular miner

Creating the area's first industry

Empire Mine Head shaft, the largest in the area

Grass Valley and neighboring Nevada City came to be because of gold. When the rush originally started in 1849 the miners largely ignored existing property rights, and they rushed to the rivers, in spots where the gold was so richly concentrated that simple placer mining could be employed. Since the gold is heavier than most other materials it tends to settle out first in areas of slower moving water. So the first minors simply panned for gold, where they would scoop up some alluvial deposits and slowly agitate and flush the pan with more water counting on the heavier gold to settle to the bottom of the pan with everything else slowly being flushed out. This was a largely inefficient process as it could take about 10 hours to process approximately one cubic yard of material. Early on when panning was in its infancy, that was not a bad proposition as there was plenty of easy gold for the picking, as they say.

Rocker box or cradle

Soon more efficient methods were adopted. A rocker box or cradle was used to process more material at a time. It consisted of a box that could be rocked that had several screens, riffles, and channels along the bottom of a tray to separate the heavier gold from the rest of the material that was slowly flushed out. It allowed the miner to process three or four times as much material at a time as a simple pan would.

Sluice Box

Next up the scale would be a Sluice box, this allows shovelfuls of material at a time to be dropped into the top of it with a source of water running through it. Again, sets of riffles along the bottom of the box would trap the gold. While this can process lots of material it is claimed that they only recovered 40% of the gold shoveled into it. So, the tradeoff was more material could be sifted through at a time, at the expense of gold that went unrecovered. But volume of soil processed won out.

By 1850 most of the easily accessible gold had been collected. Now gold miners got more aggressive about hoarding the sites that still might harbor easy to harvest gold. There were some organized attacks on foreign miners, especially Latin Americans and Chinese. The newly founded California Legislature in 1850 passed a foreign miner’s tax of $20/mo. That would be over $600/mo today.

Besides the diseases the outsiders brought, the miners forcibly started evicting Native Americans from their lands. Some responded by attacking the miners. This led to attacks against native villages. Being outgunned led to massacres of the natives. Those surviving often starved without access to their food gathering areas.

This led to a temporary military post being erected southwest of Grass Valley, near present day Marysville. For three years Camp Far West as it was known, was strategically placed to safeguard the travel routes to the area's mines. The post's commander Captain Hannibal Day, noted that the hardy and well-armed miner was being defended by an under-fed and scurvy-weakened soldier from "a miserable race of savages . . . armed only with the bow and arrow." That said much about the plight of the natives and their treatment.

Over time the individual miner gave way to industrial scale mining as most of the easily accessible surface gold had been recovered. One of the three ways of accomplishing this was with Hydraulic Mining. By 1853 this new level of intrusion to extract gold was in use. Hydraulic mining, employing jets of high-pressure water were used on gravel beds that flanked the river, but also on entire hillsides and bluffs. The loosened gravel would then pass over sluices. This resulted in large amounts of gravel, silt, and other materials to be washed downstream. The major economic advantage to this method was overhead. Hydraulic mining took one quarter of the manpower that other types of mining took for the same amount of gold extracted.

High Pressure mining: The loosened gravel would then pass over sluices (red)

Where this type of mining was done still bears the scars today, as the topsoil has been washed away and the underlying rock does not support vegetation. One of the worse examples of this type of mining is only a few air miles north of Grass Valley on the other side of the South Yuba river canyon on a ridge separating the Middle and South Forks of the Yuba River. This area became known as the Malakoff Diggins. In 1866 the North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Company was formed to mine this area. By 1874 they had carved a 7,800 ft long drainage tunnel through a ridge to facilitate the processing of 50,000 tons per day of gravel set loose by seven giant "monitors," giant water cannons, working 24/7. To allow the round the clock operations, an early use of high intensity electric light was installed. The waste tailings, also called slickens, were dumped into the Yuba River, which eventually destroyed farmland as far down stream as Sacramento.

Much of those tailings can be found downstream where they choked rivers and stream beds. Some areas downstream saw those beds raise approximately 100 feet. The I street bridge in Sacramento had to be raised 20 feet. Eventually this situation led to one of the first environmental court decisions. The Sawyer Decision, named after the judge who handed down the ruling, caused this type of mining to cease in 1884.

One result of this type of mining was the invention and implementation of river dredging to clear out debris in the waterways all the way down to the San Francisco Bay. This dredging was also applied to the Yuba River near Marysville. But by 1904 onward most of the dredging was done away from the river in what came to be known as Yuba or Hammonton Dredge Field, named after the man who started in the area with two dredges.

Long abandoned but still floating. About 20 miles downstream from the Grass Valley area.

The dredges appear much like industrial versions of a flat bottom riverboat with a bucket line conveyor in the front that would scoop up material and convey it into the boat where it usually was dumped into a circular rotating screen sloped downward. As the material traversed down this screened tunnel it first encountered a small mesh screen to allow the fine material, including gold to filter out. As the material continued down the tunnel it encountered larger mesh screen to let the large chunks or rocks fall out. The fine material fell into a sluice box, which worked as other smaller ones used alongside streams. All the material that was discarded, the tailings, were expelled out the back by a spreader or stacker as it was called and was left behind the boat as tailing piles.

The boat would reside in its own man made pond, digging its way forward and filling in the leftovers behind it. The pond literally only surrounds the boat and moved forward as the boat dug its way forward. Much gold was left behind, and in some instances, the same ground was literally plowed through again. But by the late 1960s the extraction of gold became uneconomical and the search for gold stopped. But recent satellite photos still show a couple vessels sitting in these artificial ponds, supposedly now digging out aggregate to produce concrete. This area from the air is said to resemble a vast network of intestines. The field is about four miles long and extends a little over a mile south of the river and is about 15 miles downstream from Grass Valley.

This was not the only area nearby that underwent the dredging process. About 50 miles south of Grass Valley, on the edge of the eastern Sacramento Valley was the Folsom Gold Field. This was along the American River, most of it south of it. It stretched 10 miles downstream to the Sacramento suburb of Fair Oaks, and south from the river by six miles. It had dredging operations into the early 1960s. The Aerojet rocket engine company settled in the area, as they found the tailing piles made good abutments to retain rocket blasts during testing.

While none of the others were anywhere near as massive and invasive as the Yuba and Folsom fields, many rivers flowing out of the central Sierras had dredging efforts where those rivers met the valley to capture gold that was being wash out of the mountains downstream, by natural forces, or the gold set loose during Placer mining but not actually recovered in the mining process. It is estimated that most of the gold dug up was lost downstream.

The third and most enduring way to extract industrial volumes of gold, mining had to go underground. Miners started engaging in "coyoteing." Digging a shaft 20 to 40 feet deep into deposits near a stream, and then tunneling out from the shaft. Gold mining continued to get more sophisticated and destructive. Miners at times would divert a creek away from its current streambed and into a sluice beside it. They would then dig out the exposed streambed. But some those shafts and the tunnels radiating out from them got much deeper and longer. Deep shaft mining rapidly became the way to recover gold in the area.

There were three big deep shaft mines that survived a fair ways into the 20th century, and we will look at them now. One owner, who ended up owning the two largest mines, looked outward from the Grass Valley area, while the other concentrated his gaze locally. As we will see one inadvertently greatly changed the trajectory of the area from a technological standpoint.

The Big Two Mines

The largest two mines in the area, first the North Star, and later the Empire came to be owned by William Bowers Bourn II. What helped kick start the large mines in the area was that capital and new mining technology flowed back to the area after the Comstock Lode silver mining area in Nevada declined in the mid-1870s. This silver strike, about 80 air miles east of Grass Valley was made by a company of Mormon emigrants and for a while enticed a lot of would be gold prospectors to become silver prospectors.

The other catalyst for these mines were the Cornish that came to the area. The area still has a Cornish influence to this day, including an annual Cornish Christmas Festival held in Grass Valley. For several years in the 1850s deep shaft mining stalled at a shallow depth. The problem is when you dig deep and get below the water table, water will insidiously try to fill the dug-out voids. Enter the Cornish, or Cousin Jack's and Jenny's as they were called. The Cornish immigrants brought hard rock mining experience and technology from the tin and copper mines of Cornwall. The tin mines in England had collapsed due to cheaper production in other parts of the world. These were miners that knew how to keep deep shafts dry, and had developed the needed pump technology, and each steam-powered Cornish pump could draw out 18,000 gallons of water per hour. The first Cornish pump was installed in an area mine in 1855.

By 1861 most of the hard rock mining was carried out by the Cornish, and they began to form a distinct community in Grass Valley.

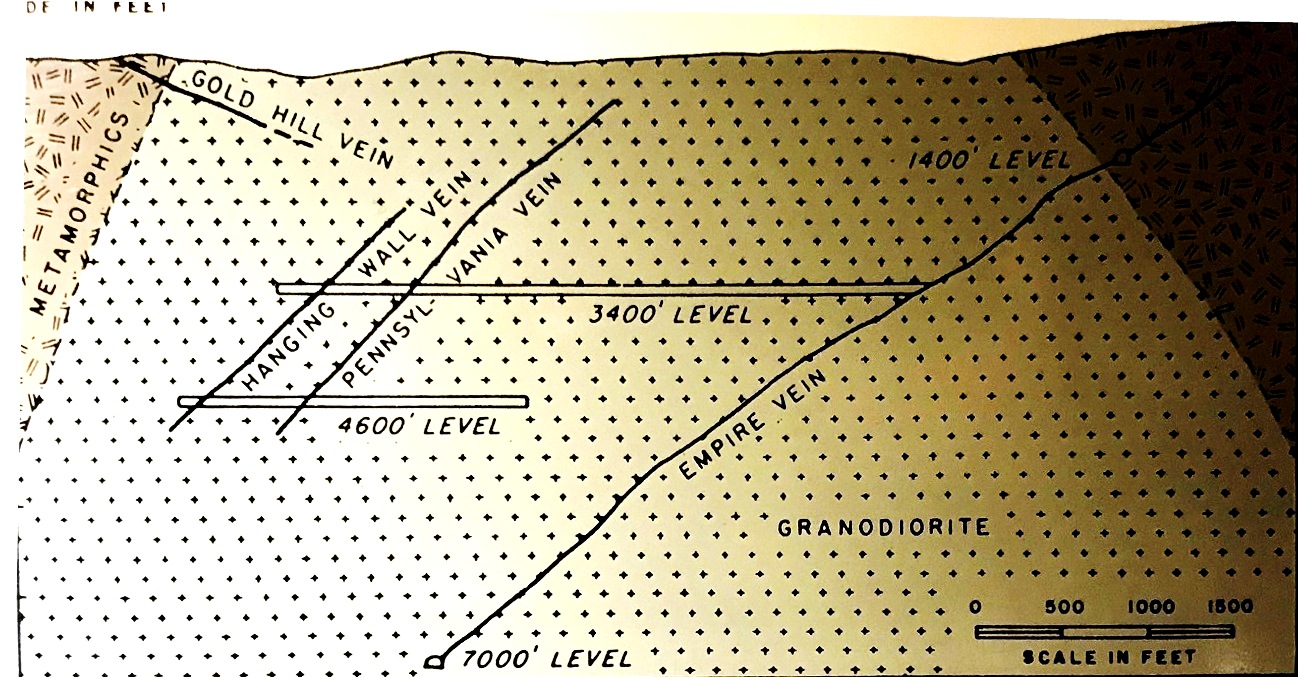

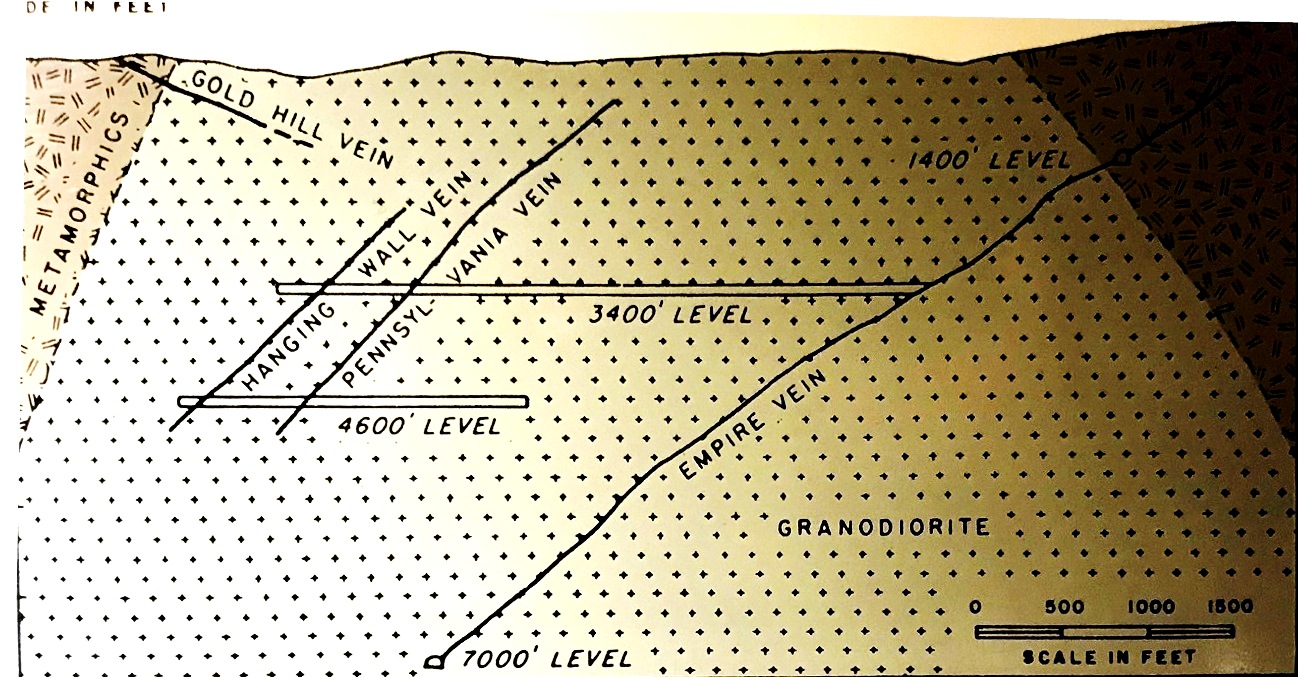

The Empire mine is the oldest, largest, deepest mine in California. It has 367 miles of tunnels. Between 1850 and its closure in 1956, the Empire Mine produced 5.8 million ounces of gold. It is believed that the underlying rock in the area contain between three and seven ounces of gold per ton. In 1854 the mine site was incorporated into the Empire Mining Company. Apart from World War II, the mine continued in operation until 1957. There were several times when the mine appeared to have reached the end of its productive life, in the 1870s, and 1890s. But new technology, and often simple perseverance would prevail over defeat and the mine would soldier on.

Cornish Festival

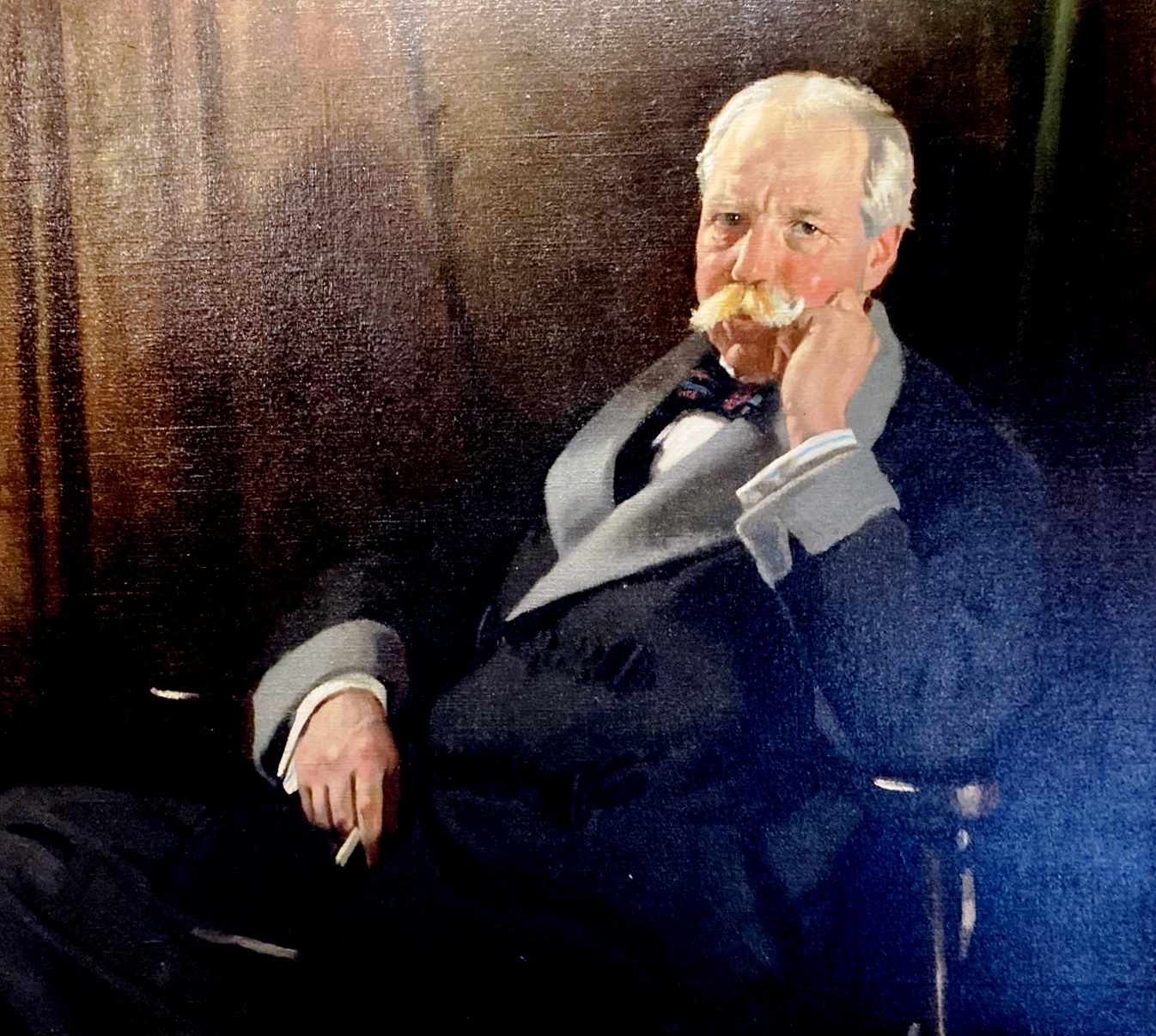

Bourn and his mines

William Bowers Bourn II

Technological advances in gold Mining over time included the invention of dynamite in 1867, which replaced more volatile black powder, and the Burleigh mechanical drill in 1869, both of which created a technological revolution in the mining industry. Due to the hazardous rock dust these drills created however, the drills, also called widow makers, did not come into widespread use until the 1890s. Miners unions successfully resisted the widow makers until then, when the devices were finally designed to be less dangerous.

The mine reached a death of 1600 feet in 1886, and 115 men were employed underground, with eight at the stamp mills. The mine used a Pelton water wheels, which were extremely efficient at extracting the waters impulse energy, to power the stamp mill. The efficiency of the Pelton wheel meant that it would work in creeks where the flow of water would not be enough to power wheels of traditional design. Pelton’s wheel used cup shape blades instead of flat ones that had several funnels pointed at them that concentrated and thus increased the water pressure hitting the modified blades.

In 1888 after a couple of men were killed in a blast that destroyed much of the surface infrastructure of the mine. Tensions between labor and management ran high.

In the 1890s technology enabled many more deposits, especially large but low-grade accumulations, to be profitably worked. The improvements of air drills, explosives, and pumps, and the introduction of electric power lowered mining cost greatly. In 1890, the same year in which Cornish immigration reached its peak, the mine introduced new compressed air powered drills that allowed rapid drilling without creating the hazardous dust of earlier models. While these advances allowed for cheaper, safer mining, it required fewer miners.

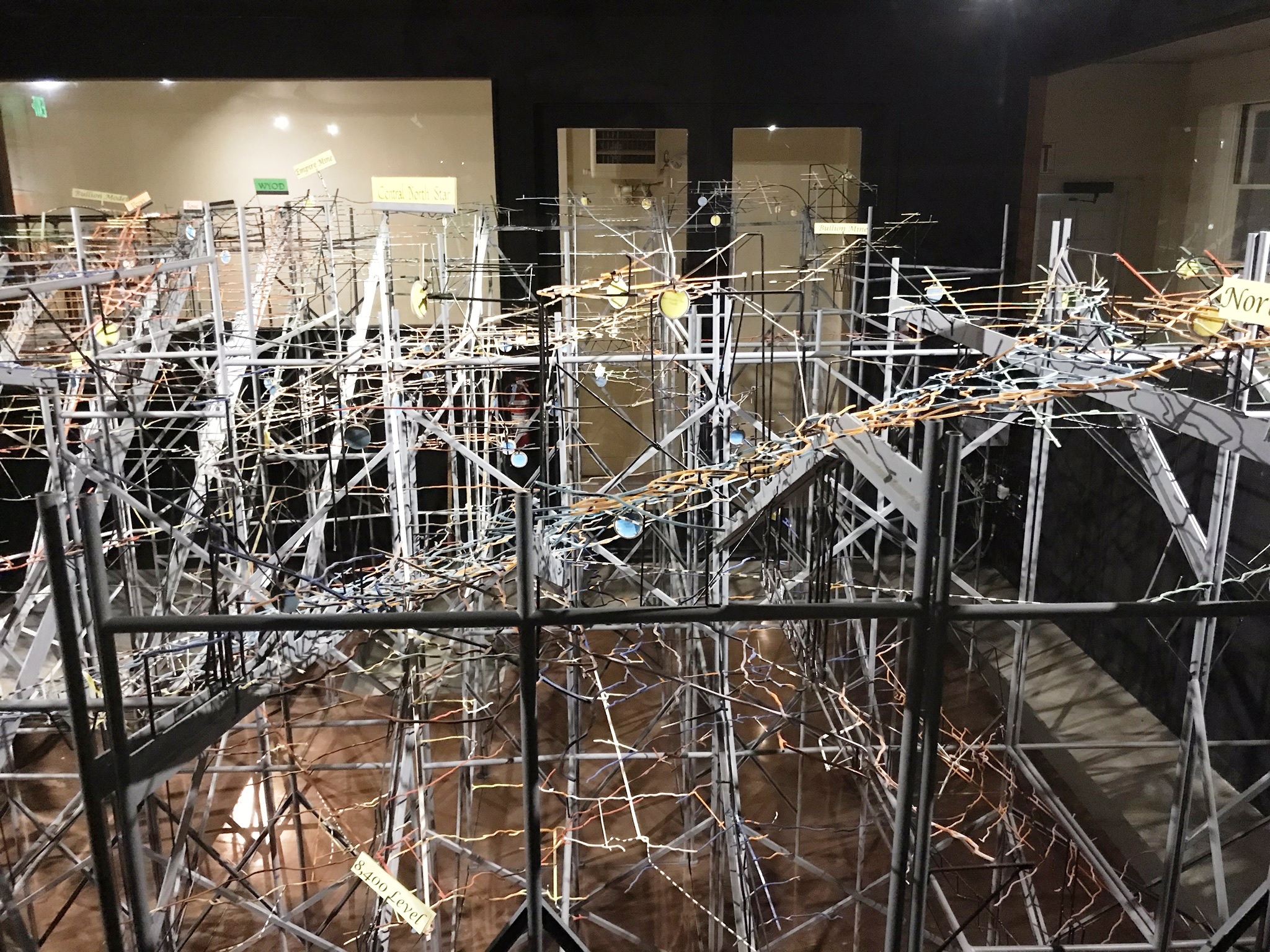

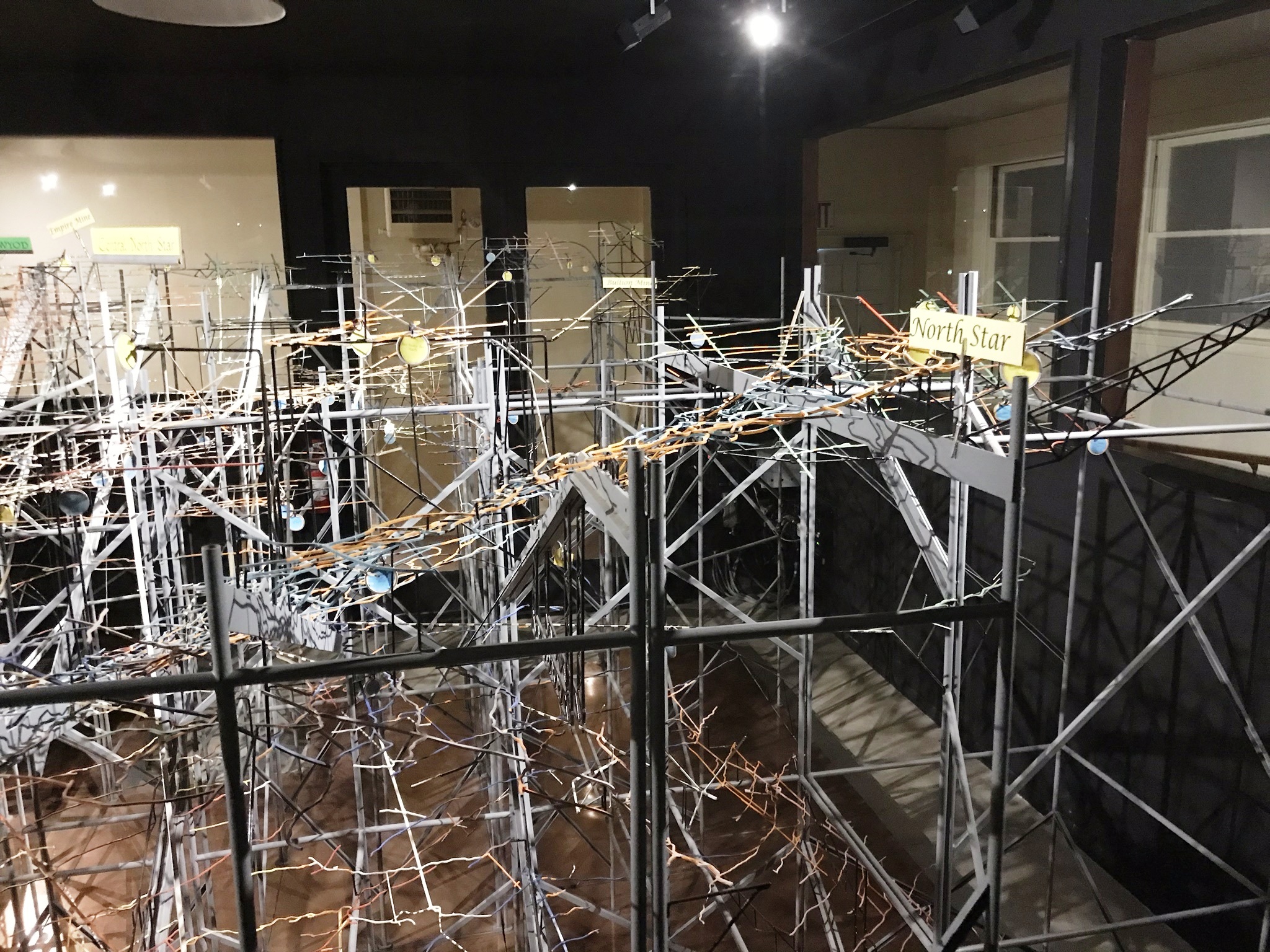

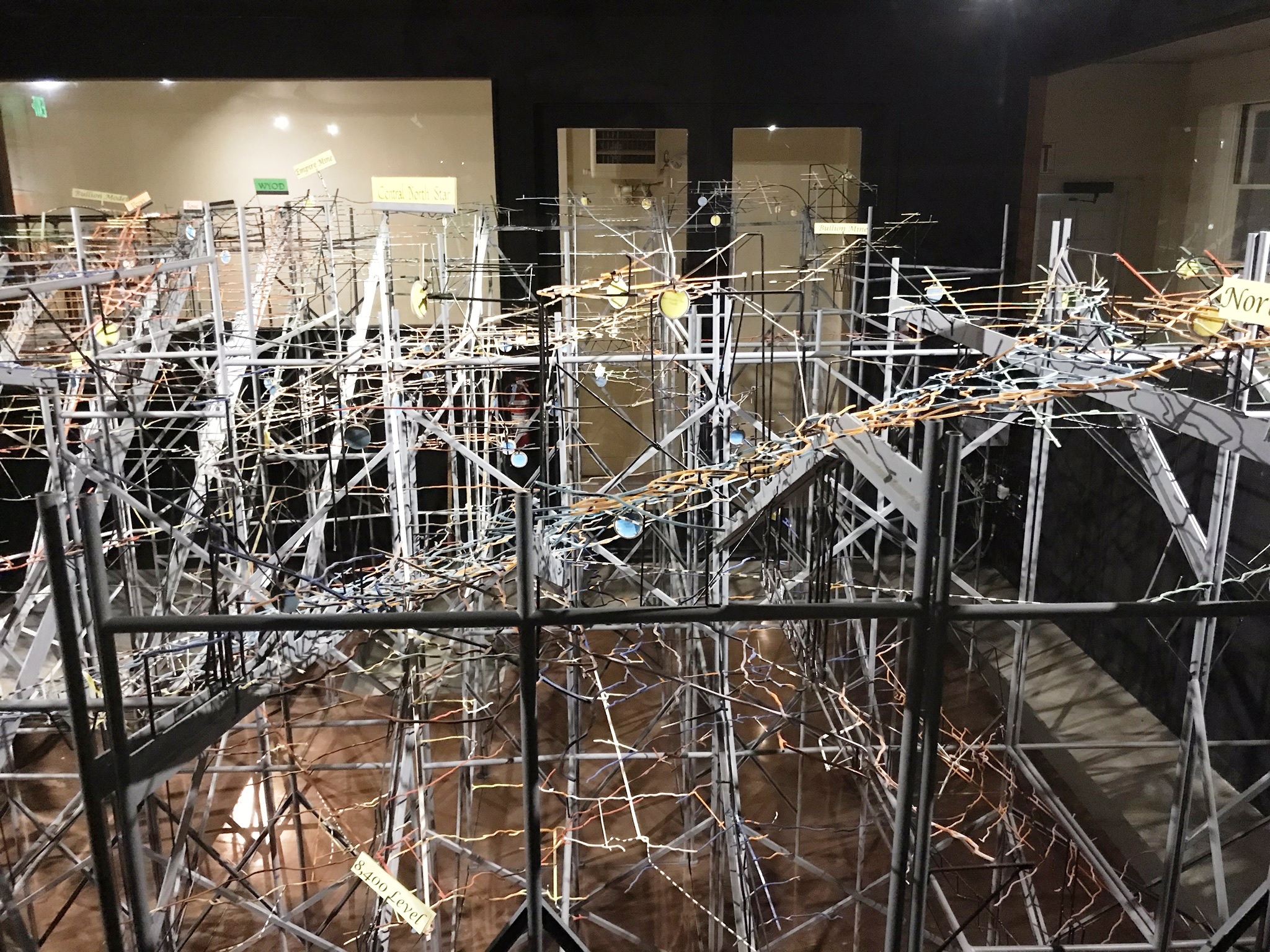

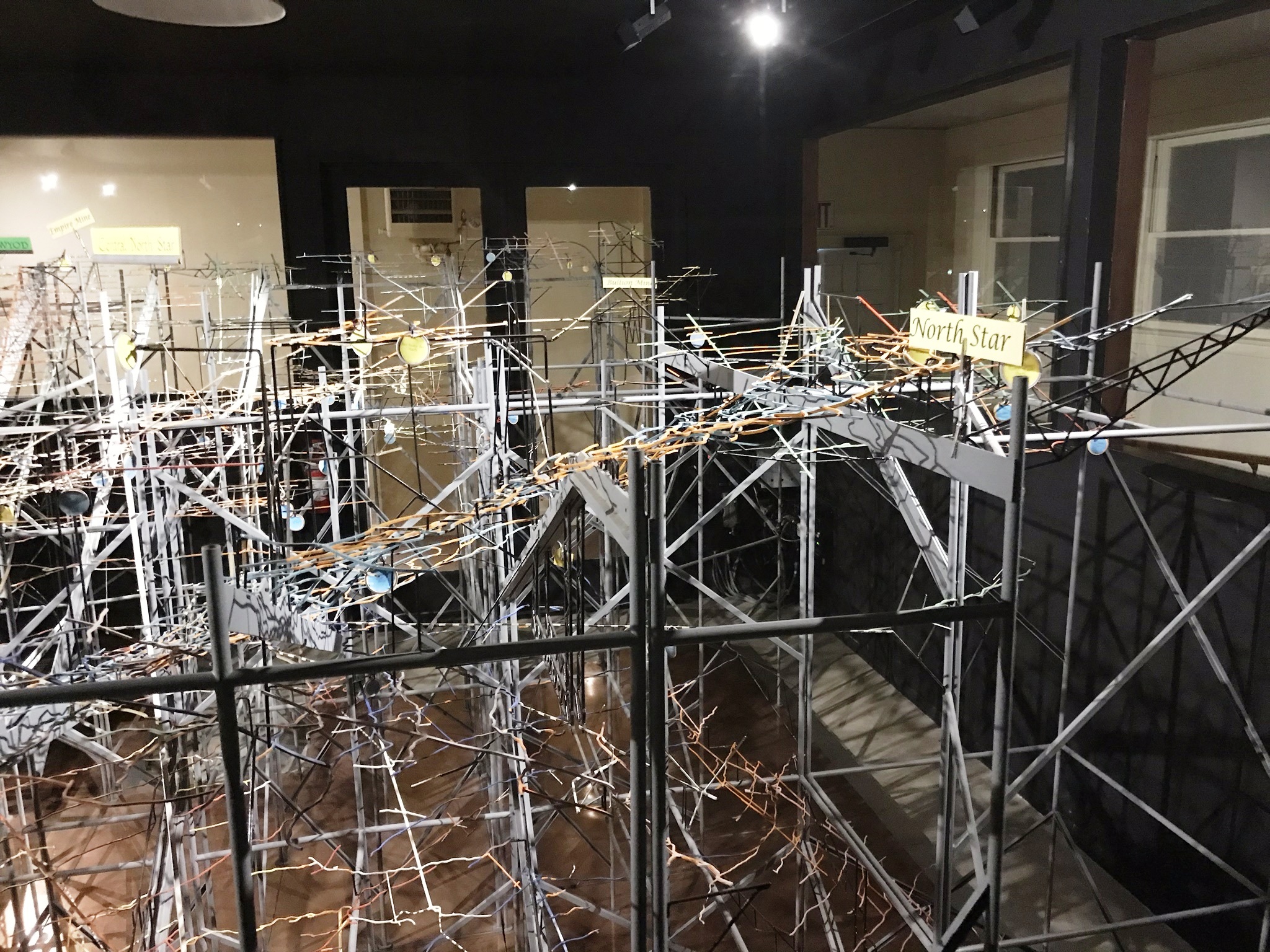

Empire mine model: The mine was so complex and intertwined with others that a secret 3D model of the intricate labyrinth of shafts and tunnels was constructed. It is now displayed in the Empire Mine State Park's museum.

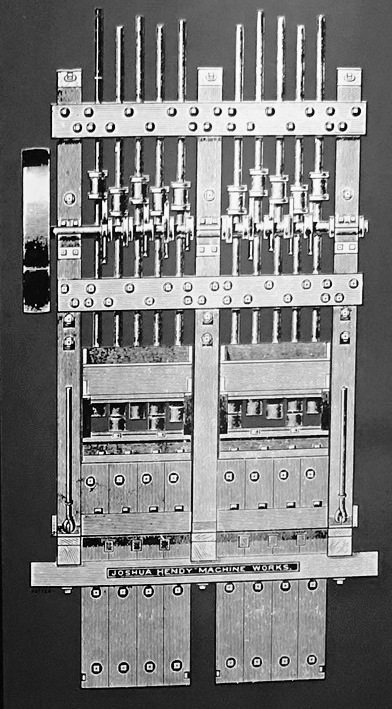

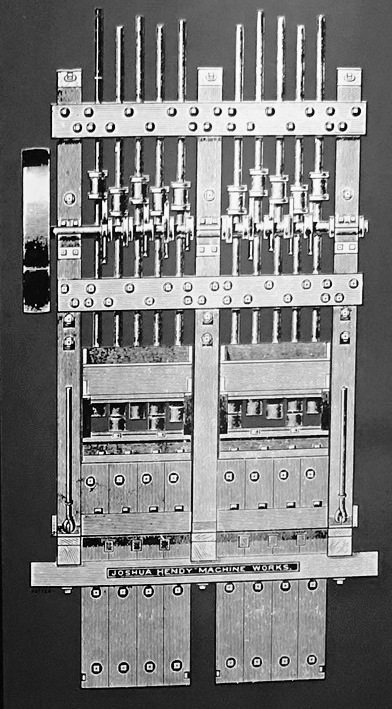

In addition, the introduction of better rock crushers, allowed increases in the size of the stamp mills, and new concentrating devices, lowering milling costs. Stamp mills reached peak size in efficiency, that is the amount of material processed and the percent of gold recovered, during the 1880s and 1890s and were typically powered by electricity instead of water after 1890.

Stamp mills

It was noted that the mines increase in wealth as increased depth was attained. The deepest mines were the richest ones. Many argued that gold mining in general came of age or reached maturity around 1870. Gold mining around the Grass Valley area, however, appears to have reached its peak during the gold mining boom period of 1898 to 1916.

Right before this local peak, the Empire mine, in the early 1890s, encountered a barren zone. The owners did not want to invest in the mine during this period. The facilities deteriorated considerably, and by 1895 the mine only employed a few men, with about 100 working on shares in the mine. The company operated at a loss from 1893 to 1898. At which time the barren zone was penetrated through and the vein re-located. By January 1899, a vein was found that was so rich that it paid for all the recent mines improvements and even yielded dividends.

Empire Mine Gold Veins

The Empire Mine acquired other nearby mines and crosscut over to them, joining these mines into ever larger complexes. In their zeal the other big nearby mine to the west, NorthStar, in 1914 claimed that Empire had dug into their claim. The complaint was settled out of court, but it was around this time that the owners of the Empire mine began to hold the entire operation under a veil of secrecy, consistently refusing to supply data to the state’s mineralogist. One observer said that the owners demand for secrecy, the refusal to give data to state commissions, and the Empires policy of storing wash underground and with the mine depth pushing towards 4,600 ft, the prohibition of visitors below the 3000 foot level, one wonders how many other wandering tunnels were dug. Eventually the mine would reach a depth of 11,000 ft.

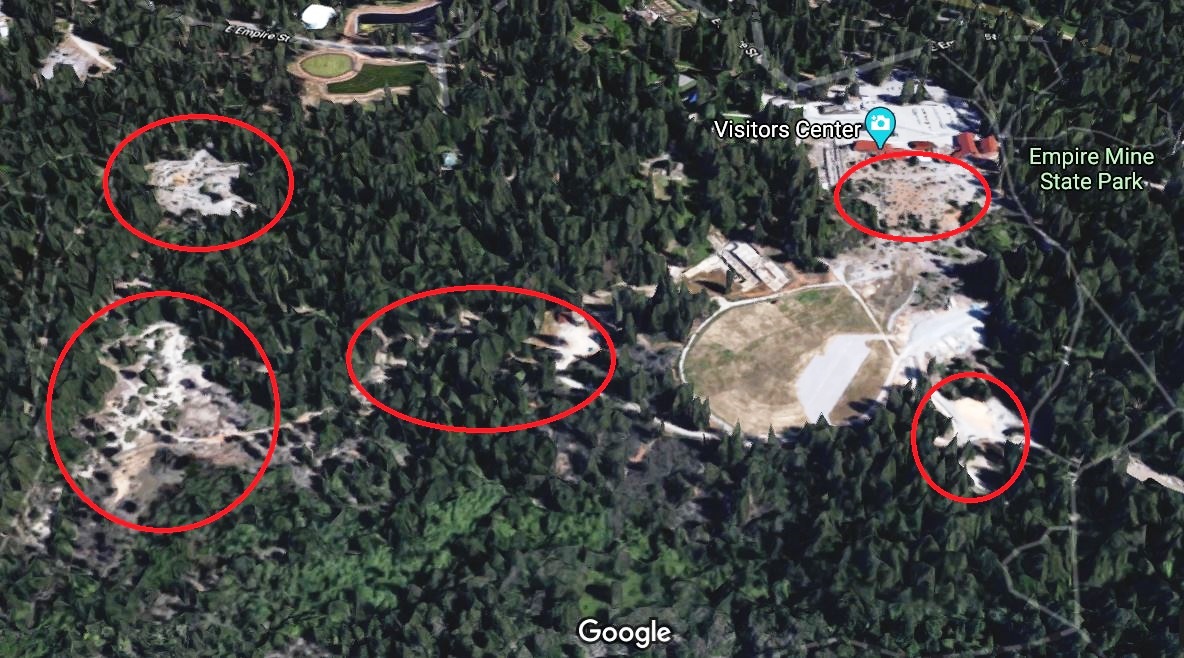

Up until 1917 the Empire mine was cavalier about getting rid of its tailings, the material that was screened for gold. Most of it was simply dumped into nearby Wolf Creek. The California Debris Commission then required the mine to impound its mill tailings. In response the company built several ponds to dump the tailings into, and also created a few piles of material the size of small hills. Today these remnants are considered environmental hazards that have slowly been undergoing remediation.

Empire Mine Tailings

Economic inflation that occurred after the first world war inflamed conflicts between labor and the mines, resulting in strikes at the Empire and the North Star in 1919. In 1918 a miner was paid about $3.25 a day, after the strike they made $6 a day. Tensions continued in the early 1920s. Another source of conflict is that the mines were still consolidating, and the Empire bought another nearby mine and looked to close its separate mill operation and install a subterranean electric train to transport the ore directly to the Empire’s Mill eliminating the jobs in the redundant mill.

Also during this time the mine purchased property northeast of the mine towards the center of Grass Valley and presented it to the city in memory of those who did not make it back from the war, which became Memorial Park.

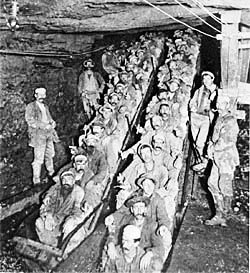

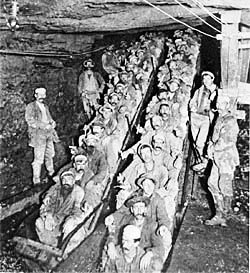

Going to work

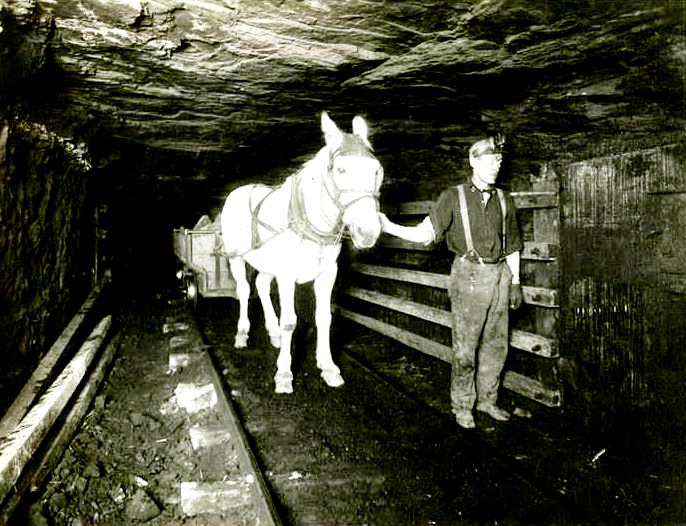

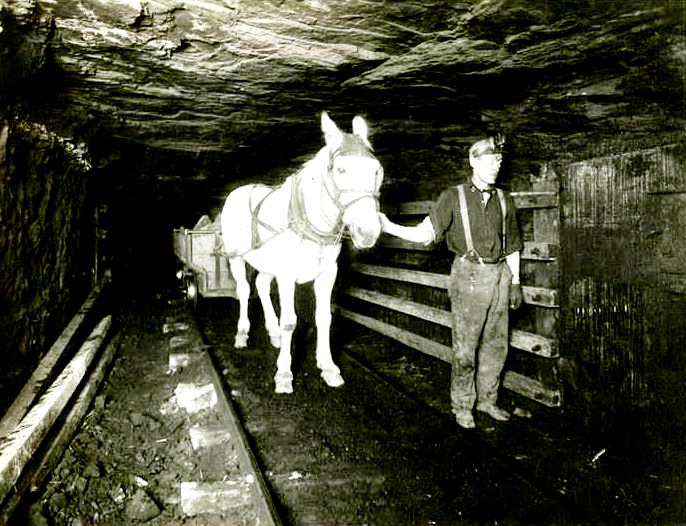

Mules

Up until this time mules were housed within the mine labyrinth had been doing much of the underground hauling. There were over 40 mules employed that pulled ore cars to a chute for hoist out. Many of the mules spent 30 years in the mines, never seeing daylight. If they got sick, veterinarians attended to them in the mine. The only time the mules made it to the surface were during strikes. When that happened, the mules were blindfolded and slowly allowed to adjust to the light.

In 1923 there were 400 minors working for the Empire Mine. Some tried to supplement their income by smuggling small amounts of gold out of work in their clothes. In the 30s that led to a rigid inspection system after a few workers managed to sneak out a few hundred thousand dollars’ worth of gold. The workers on exiting had to leave all their work clothes in one room after their shift and walk naked to another room to retrieve them.

In 1929 the Empire and North Star mines merged. Combined, these mines made the complex the number one gold producer in the state in 1930. On top of that by the end of 1930 a new vein at the Empire was found.

The French Lead, or North Star vein, was discovered in the Fall of 1851 by a group of French prospectors. It passed through a couple owners before it was purchased for $15,000 by the owners of the North Star Group in 1860 and was renamed the North Star Quartz Mining Co. in 1861.

Pelton Water Wheels

This invention was a large leap forward in industrial mining. Hard rock mining required power to drive machinery such as rock crushers, stamp mills, hoists and compressors. Prior to electricity, the only source of such power was water or steam.

At that time many mining operations were powered by steam engines which consumed vast amounts of wood as their fuel. Some water wheels were used in the larger rivers, but they were ineffective in the smaller streams that were found near the mines. Pelton worked on a design for a water wheel that would work with the relatively small flow found in these streams.

The Pelton wheel was developed to eliminate resistance of incoming water caused by splash back. This wheel extracts energy from the impulse of moving water, as opposed to water's dead weight like the traditional overshot water wheel. Many earlier variations of impulse turbines existed, but they were less efficient than Pelton's design. Water leaving those wheels typically still had high speed, carrying away much of the dynamic energy brought to the wheels. The wheel's paddle geometry was designed so that when the rim ran at half the speed of the water jet, the water left the wheel with very little speed; thus his design extracted almost all of the water's impulse energy—which made for a very efficient turbine.

The Pelton wheel water turbine was invented by American inventor Lester Allan Pelton in the 1870s. He came west from Ohio for the gold rush. Pelton worked by selling fish he caught in the Sacramento River. In 1860 he moved about 50 miles northeast of Sacramento where he built the first Pelton turbine in Camptonville in 1878. He soon moved his tests, then his family, to nearby Nevada City where he perfected the wheel at the foundry.

As electric power replaced water, Pelton Wheels were later used to generate electricity. They were used worldwide and some are still in operation today.

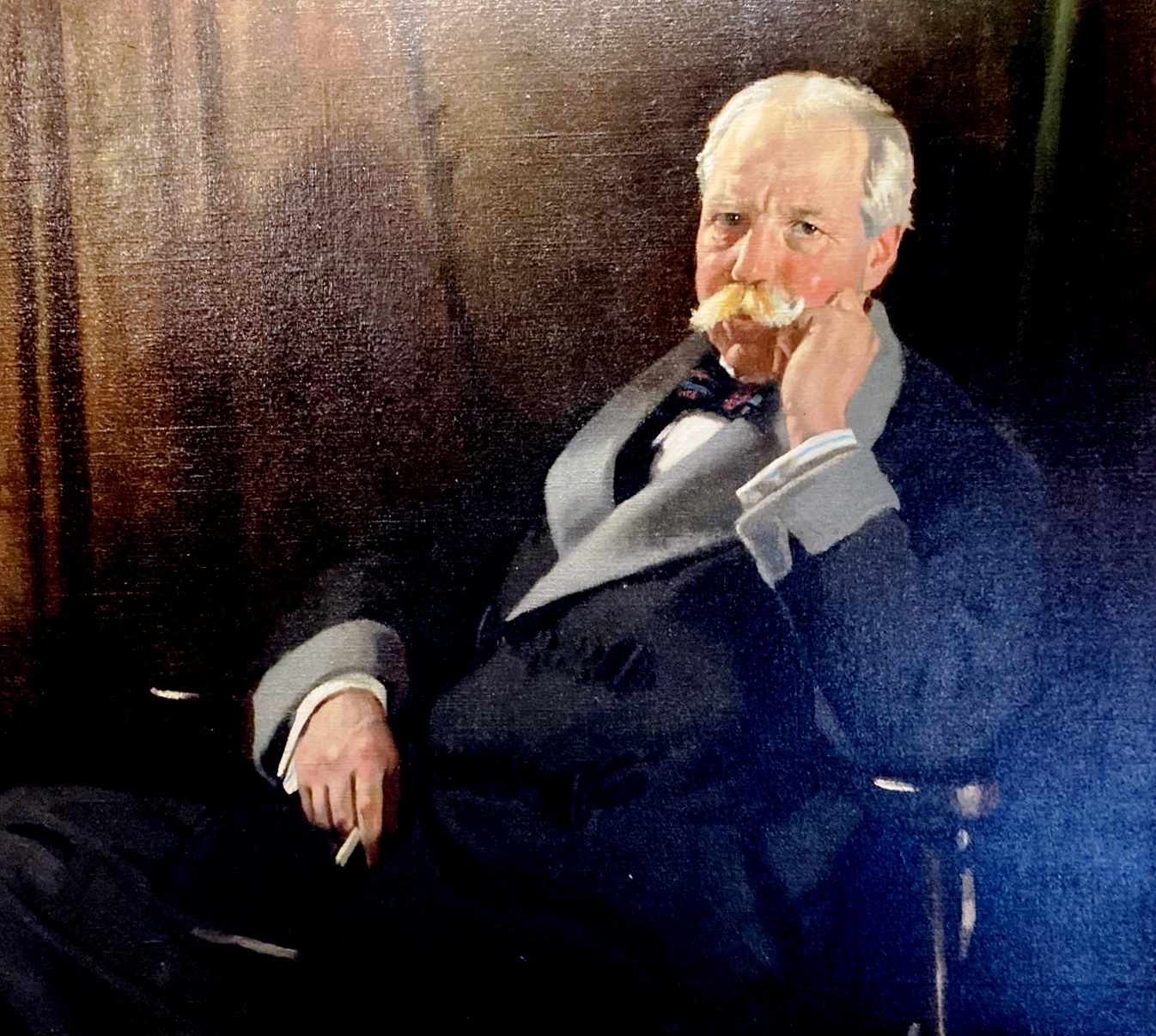

William Bowers Bourn acquired control of the Empire Mine in 1869. He died 1874 after an accidental self-inflicted gunshot wound. His estate ran the mine while his son, William Bowers Bourn II, went off to Cambridge.

The son returned to California in 1878 to help his mother run the mine and other business interests left by his father. He is credited with significantly improving the mines operations. Bourn purchased the North Star Mine in 1884, turning it into a major producer.

He also started a local bank and became a director in a San Francisco gas company. He later was instrumental in getting that company to merge with an electric company that eventually became Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), a major power utility in California.

In 1887 he sold all his mining interests. The new owner reorganized the company as the North Star Mines Company in 1889, and acquired several nearby mines. At one time the Empire and North Star complex was the second largest producer of gold in the state.

Greystone Cellars

Bourn next looked to change the Napa County wine business. He and a partner gained support of local vintners to build a cooperative winery. At the time, most area vintners did not have the capacity to store and age wine, and so wine was sold to dealers, who had the storage capacity. It was sold to the dealers at extremely low prices, as little as 15 cents per gallon. Using his mining experience, he built the Greystone Cellars facility that included 13 tunnels into the hills behind the cellar. The building and tunnels could hold three million gallons of wine. It was described as the largest wine cellar in California, perhaps the world. In 1894 an enduring Grape phylloxera he sold the building at a low price.

There is another tie between the New Almaden mercury mine and the North Star mine besides mercury. A mining engineer, Arthur Foote, worked for the New Almaden mine early in his career, 1876, and retired from that career as the Superintendent of the North Star Mine in 1913. His career at the North Star started in 1895, where he was instrumental in installing a large Pelton Water Wheel. He decided that to power the mine with electricity would neither be reliable or safe. So, he used the Pelton Wheel to drive air compressors which powered the drills and other mining equipment. He commissioned the wheel to be 60% larger than the maximum Pelton recommended themselves. The wheel was in service for over 30 years. His wife, Mary Hallock Foote, was a well-known author and illustrator who wrote about life in the west for her main audience, people in the east. Arthur brought her out from the east when he married her while working at New Almaden. Originally, he was from Connecticut and she from New York state.

Foote Mansion

Two of the landmark mansions in the Grass Valley area are known as the Bourn Cottage, hardly a "cottage," and the North Star House, also known as the Foote Mansion. The Foote's commissioned it in 1905 and it was designed by architect Julia Morgan, this project being her first significant, large scale residential building. She would go on to design hundreds of buildings in California, including her work as the architect of Hearst Castle, a project that spanned from 1919 to 1947, only interrupted by the war. She was called "America's first truly independent female architect." The residence was neglected in the 70s and 80s and then refurbished and is today used as an event center.

He then turned back to the Empire Mine, regaining control in 1896. In 1898 the mine installed the largest ever Pelton wheel to power the mine. Located along Wolf Creek, at the southern edge of Grass Valley it is only a mile west of the Empire mine.

Their wealth accumulated from the richest gold mine in California put William and Agnes Bourn in the class of Americans depicted in a F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel. Extensive travel allowed them to refine their tastes in cultural centers of Europe. They rested and played only in the most pristine alpine centers on the continent, and in North America.

Bourn "Cottage"

They acquired outposts around the San Francisco bay area, and across the Atlantic:

I)The cottage, built at the Empire Mine that was intended to be used for short stays during the summer due to the noise from the mines nearby stamp mills. The cottage and 13 acres of surrounding gardens were designed by Willis Polk, a well-known San Francisco architect. The cottage itself was 4,500 square feet. Small by Bourn standards.

II) An estate in what is now the Killarney National Park, in Ireland

III) A mansion in Pacific Heights, a neighborhood in north central San Francisco

IV) An estate on what later became the 17-mile drive in Pebble Beach

Where he put the vast majority of his wealth - Hint: It wasn't in Grass Valley

The entrance to the Filoli "gardens"

V) A "country" house, Filoli, on 670 acres, of which 16 were formal gardens, in Woodland, just south of San Francisco

The front door

One of the Libraries

The Ballroom

An "intimate" dinner

Besides his estate in Ireland, which he bought as a gift for his daughter and her husband, which Bourn and her daughter's husband donated to the Irish government in 1932 in memorial of the daughter's passing, his other palatial estate was Filoli, built in 1915. It is at the south end of a reservoir, Crystal Springs, up against the Santa Cruz mountains. The reservoir and estate sit in a rift valley caused by the San Andreas fault. An interesting contrast is that it was a fault that formed the Sierra's mother lode, which Bourn got rich off, and he ends up building on the mother lode of faults.

Water Temple

Bourn was a major stockholder in the water company that owned that reservoir, the Spring Valley Water Company. The company owned a monopoly on San Francisco's water supply. The company owned much of the Alameda County's watershed, plus parts in Santa Clara, and San Mateo counties, which all ring around the bay. San Francisco tried to buy the company for almost 60 years, and finally succeeded in 1930. Many thought that Bourn's water company, and Bourn himself were guilty of charging too much for their service. The sale happened in part because San Francisco had gained the water rights to the Tuolumne river in the extreme northern part of Yosemite. It took presidential and congresses' support to secure those rights. A valley, Hetch Hetchy, which some claim to be a close cousin of Yosemite Valley in beauty, was dammed, work on the dam commenced in 1914 and was completed in 1923. The water first made it to San Francisco in 1934, after ownership of the Bourn's water company was sold to the City of San Francisco. The project was controversial then and continues to this day.

Crystal Springs

Another catalyst for Hetch Hetchy was the 1906 earthquake which exposed that the city did not have enough water capability to fight the fires, which caused more damage than the earthquake did.

The earthquake made Mrs. Bourn uneasy about living in their house in San Francisco proper. So, it is ironic that they built Filoli on the fault that caused all the damage.

When the 1906 earthquake struck, the Bourns were in Monte Carlo, France. William Bourn cabled money he had won at a casino to family members in San Francisco. He and his wife took the next train to Paris and then the next ship to New York. They hastened back as quickly as possible, but the journey still took three weeks.

"One does not realize the awful calamity from the Bay," Agnes wrote. When they disembarked off the ferry from Oakland at the city’s Ferry terminal, which stood reinforced by scaffolding, the magnitude of the destruction was evident looking up Market Street, The Bourns' home in Pacific Heights had survived, but Agnes Bourn would never be comfortable there again.

The Bourns' spent most of 1906 up in Grass Valley as the city was a disaster zone with the constant noise of clearing debris and rebuilding. Without the need to toil every day at a regular job he worked on his tennis and billiard games. He had a clubhouse built near the "cottage" to facilitate those activities. When he did work, he thought about San Francisco and how to rebuild it more in the style of The Burnham Plan, named after the main author of a plan to reshape Chicago's center, with widen streets, parks, civic plazas, integrated transportation, and waterfront use. He was determined to defeat what he considered the petty interests who wanted nothing more than to return to business as quickly as possible. "He dreamed only grand dreams," wrote Ferol Egan, Bourn's biographer, "for to him small dreams were the nightmares of small minds and the currency of corruption."

While the earthquake had made the city think that it needed to break the water monopoly that Bourn's company had, he saw it as both a business opportunity and a way to contribute to a new, imperial city. Even though, a newspaper accused him of profiteering off the disaster.

His views of society were controversial and would never prevail. He believed in a meritocracy, which should be led by men like himself. Not necessarily wealthy men, but men of character who thought of the common good. He believed it was hardship that shaped people. "It is not the joys of life that up build character," he wrote. "Sorrow, or the appreciation of responsibility, chastens characters and lifts human nature to higher levels of thought and emotion."

He helped to plan the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition to celebrate its Phoenix like rise from the ashes. He was an early contributor and he wrested donations from the wealthiest San Franciscans. The exhibition opened in 1915. He also helped to rebuild an Episcopal Church in the city. All Bourn's efforts depended on the Empire mine, which kept generating substantial profits throughout the decade of rebuilding.

He also moved in the most ratified of circles and was elected president of the Pacific Union Club. The club sits atop Nob Hill and it and the Fairmont Hotel, which was nearly completed when the earthquake struck, were the only structures left standing in the area, although the interior of the hotel was extensively damaged by fire. Prominent names of club members include the Bechtels, Grady, Hearsts, Hewlett, Kaiser, McNamara, Packard, Schwab, and Weinberger, among others.

Nob Hill

Though the names where different back when Bourn was president the same societal distillation, where only the cream of the cream at the very top will ever see the inside, unless you are the hired help. The bylaws for the Pacific-Union Club, for example, read: "No information regarding any Club activity or function shall be released by anyone to the media." Although newspapers were not called media back then, the attitude of exclusivity was the same. If anyone was a gold baron in the area, it was Bourn, part of the ruling class, and captains of industry. He was not tied to the place where he made his money.

Most of what he extracted out of the ground in Grass Valley that went to him, or ended up feeding economies elsewhere. Human migration patterns are continually evolving. As we will see at one-point people who had "made it" financially looked to the bay area to settle in and live. Back during Bourn's time, the gaze was towards the more sophisticated bright lights of the larger cities. Especially San Francisco, and Bourn was a bay area native. He did business in Grass Valley. He considered home somewhere else. He owned numerous residential properties; the serious ones were not in the area. He had estates in the bay area. He had a "cottage" in Grass Valley.

Bourn had a stroke in 1922 and finally sold the mine in 1929. About that time he also lost the 46-year-old daughter that led to the estate donation in Ireland. He died in 1936 at the age of 79.

Next, we will look at someone who's local financial impact was the opposite of Bourn's and planted the seeds for “video” to eventually find the area.

MacBolye

I made my money here, I'll spend it here

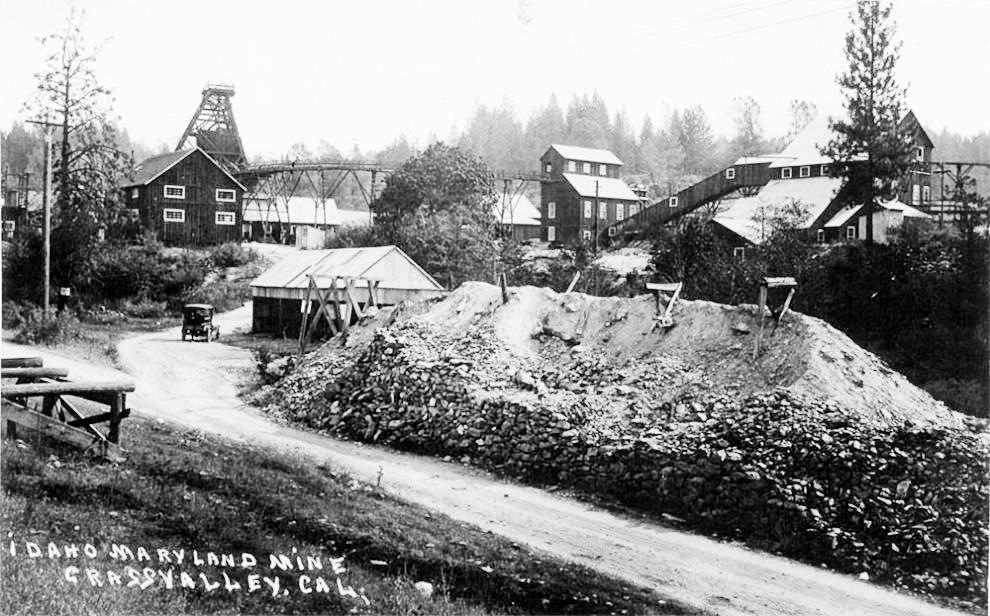

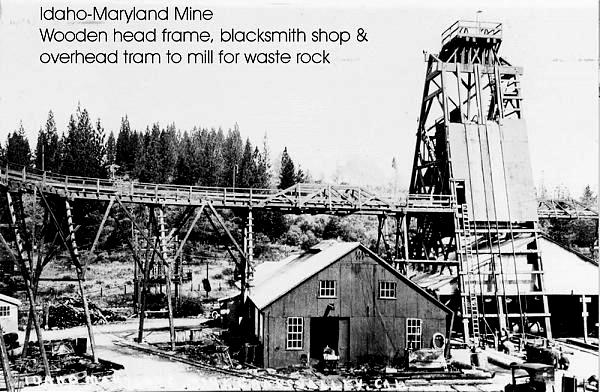

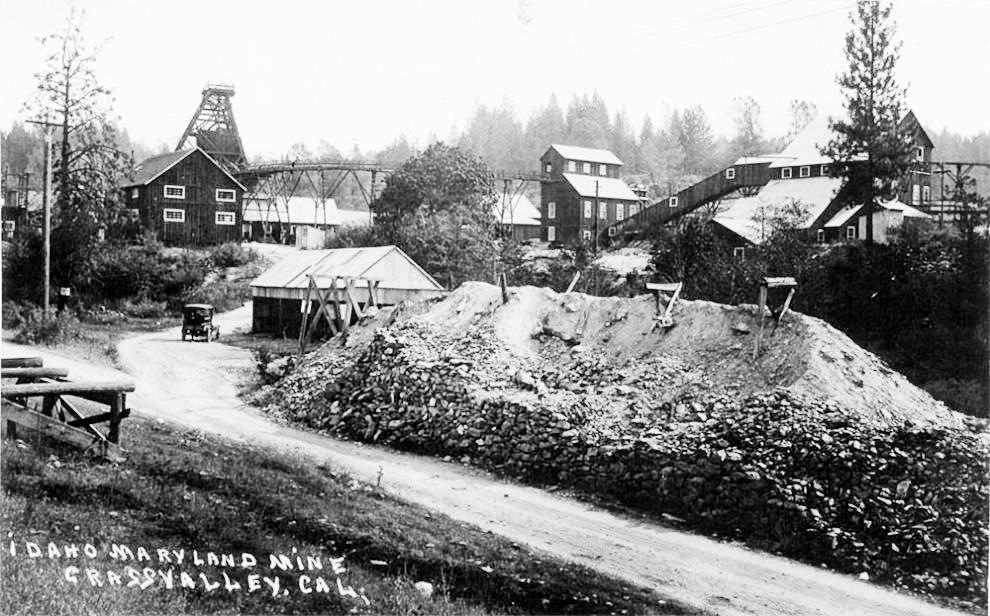

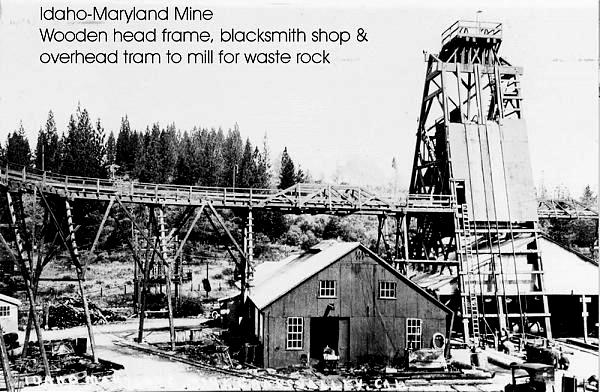

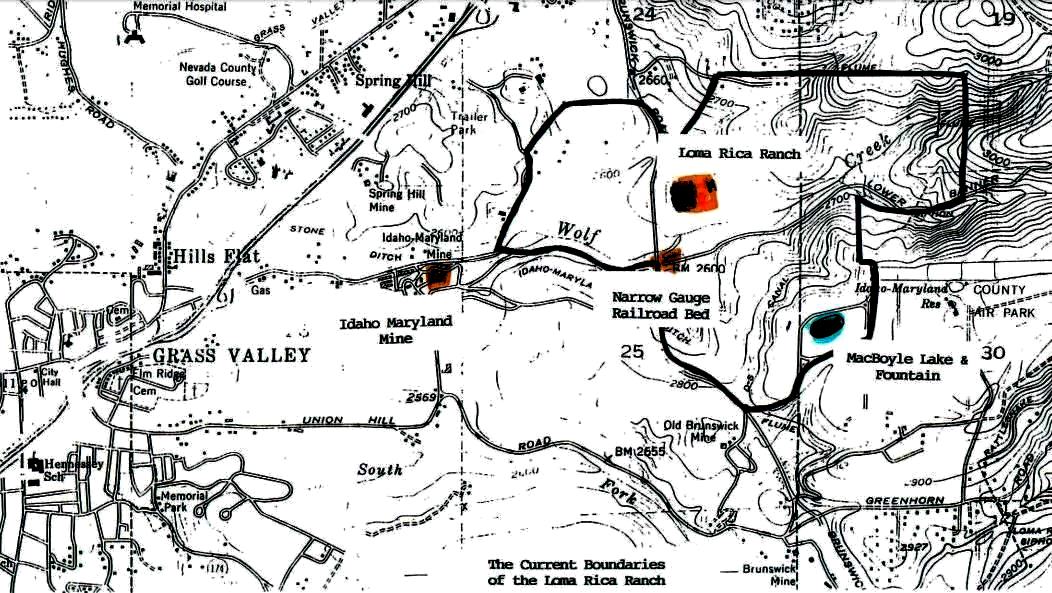

There was another large mine complex that developed in the area. Its head shaft sat about a mile northeast of the main Empire complex. It came to be known as the Idaho Maryland Mine. Today there is a road that runs alongside of the site, aptly named the Idaho Maryland Road. The complex runs under a hill to the southeast where it so happens that the Grass Valley Company, the video company, currently has, which might be, its last offices in the area.

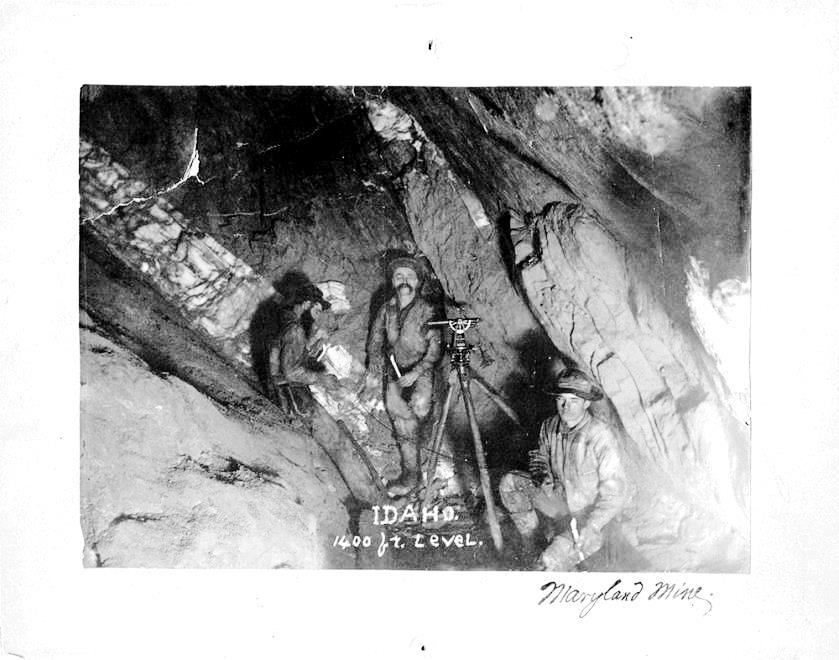

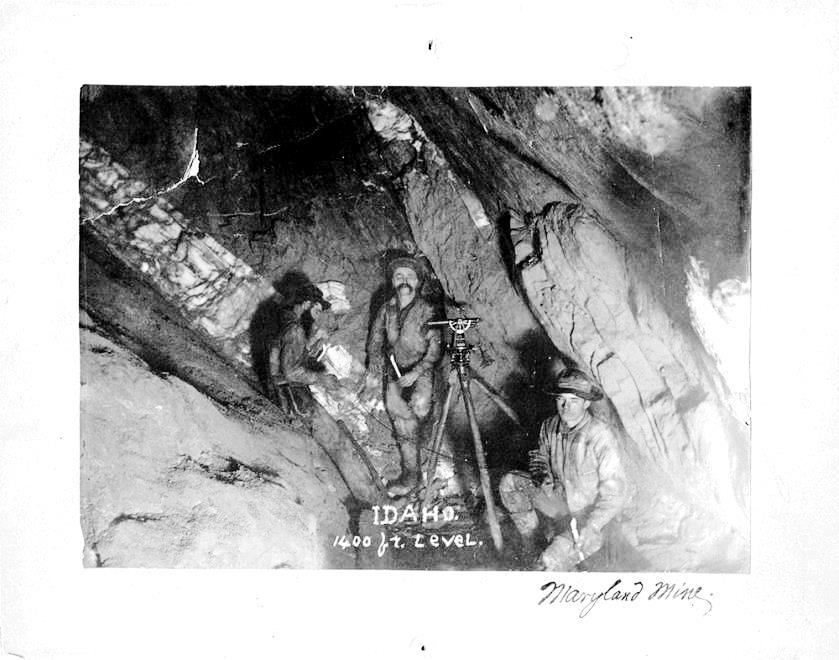

While that is not the connection between mining and video, it is a step closer. Nearby, to the southeast there is a very visible ventilation shaft and an open area where a mill site was located for one of the mines that eventually became part of the Idaho Maryland Mine complex. The Idaho claim was recorded in 1863 along Wolf Creek. Yes, the same Wolf Creek that the North Star was located on, but upstream about a mile. By 1865 a 150-foot shaft was sunk trying to reach the vein by the Idaho miners, but money ran short, and work ceased a year later. The claim was sold to the Idaho Quartz Mining Company in 1867 and at 300 feet the vein was found. By 1870 the miners are pulling ore out at 600 feet underground.

In 1872 the Idaho Mine surpassed the nearby Eureka Mine, as the leading gold-producer in California, a distinction it held until 1892. The Idaho Quartz Company recovered 574,434 oz of gold from 567,029 tons of ore extracted during this time. All activity ceased in 1893 as the Idaho mine reached the Maryland claim to the east.

The Maryland claim was staked in 1865, but serious work on it was not commenced until 1880 when the Maryland Gold Quartz Mining Company was formed. The company bought the Idaho company in 1894 and the name of the combined operations was changed to Idaho-Maryland Mine. Soon a new vein was found and ominously named after the mine's principle owner and superintendent, Victor Dorsey. A year later his son was killed in a fall down a shaft connecting two levels in the mine. He was 1600 feet down in the mine at the time. In 1901 the mine closed due to insufficient capital. The amount of gold being extracted was only about a third per year what the Idaho Mine was doing by itself earlier.

A new company, the Idaho Maryland development Company, bought the operation a year later, and after some refurbishment, namely pumping accumulated water out, shaft re-timbering, and surface repairs, resumed mining. The beginning of World War I brought an end to the operation once again. The recovered gold per year was only 1/10th what the Idaho mine was doing itself during its heyday.

Idaho-Maryland "Complex" early 1900s

MacBolye - Owner of the Idaho-Maryland mine

Errol MacBoyle, a mining engineer, took an interest in the area and with financial backing acquired a couple adjacent mining claims. After the First World War ended the Idaho-Maryland mine was brought from Dorsey and company for what would be close to $3 million in today’s dollars by the Metals Exploration company. It forms a separate company to operate the mines, Idaho-Maryland Mines Company. MacBoyle is a consulting engineer for the operation. The collection of mines now included the Union Hill Mine, which at the time was the only one being actively mined, and the Eureka mine. During the early 20s the operation continued to test drill in the mine complex, which then included the abandoned Eureka Mine just to the west of the Idaho Mine. In 1925 the mine quits operation once again.

Now MacBoyle, with his backers, stepped in and took over the Idaho-Maryland company and resumed operations. MacBoyle did this using a tribute system with the miners involved. Under the tribute system the miners furnished the labor and equipment without being paid a wage. When gold was discovered the profits were split between the miners and the mine on a 50-50 ratio.

Now there were a set of five mines combined together on the east side of Grass Valley. The Idaho and Maryland started at about the same time and were adjacent to one another. The Idaho shut down when it reached its underground claim boundary with the Maryland mine. Maryland bought the Idaho mine in 1894. In 1926 MacBoyle and his Idaho-Maryland company took over the Brunswick mine to the south by secretly buying a majority of its shares.

Errol MacBoyle was born in 1880 in Oakland, California and he went to the University of California where he majored in mining engineering. He started his career in 1902 by working a summer as a mucker at a couple small mines in the area. "Muckers" were the ones who shoveled broken rock into tramming cars. MacBoyle was a quick learner and acquired the position of a surveyor for the North Star Mine. He then traveled and worked elsewhere before settling back in Nevada County.

From 1911 to 1915, MacBoyle was an examining and reporting engineer for the California State Mining Bureau. He authored "The Mines and Mineral Resources Report of Nevada, Sierra and Plumas Counties."

One of MacBoyle's big contributions to the area was he thought he could find gold in this assembled mine complex where others could not, and as it turned out he was right. His diligence and faith in the mines paid off almost immediately with the discovery of a rich vein. 1926 was a big year for MacBoyle. Besides the first of many new gold finds, he managed to acquire the adjacent Brunswick mine to the south. That mine in the years ahead would become central to the overall operation.

In 1926 he also married Gwendolyn Clifford in San Francisco. The daughter of a plumber, she was a secretary working for a Montgomery Street law office in San Francisco before her marriage. They entertained in a lavish San Francisco residence he bought for her. She was called the Golden Lady because her house had gold lavatory fixtures and doorknobs. She resided mainly in San Francisco and had little interest in the frontier that the Grass Valley area represented, while Errol resided primarily in Grass Valley to tend to the business. But unlike Bourn, MacBoyle demonstrated more interest in looking out for the community he had gotten rich in. He said that he made his money in Nevada County, and he would spend it there.

In 1927 under his direction another even larger vein was found; 1930 yet another vein was found. The next year the company became debt free, and operations had grown to require the expansion of ore milling as the current 20-stamp mill had become a bottleneck. In the mid-30s the price of gold had increased to a point, $35/oz, that they went back to mining veins that had been considered marginal.

In 1938 recovered gold from the mine was 117,000 oz, a record for the mine. Two years later it reached 129,000 for the year. That year the USGS wanted access to the mine, among others, to study the geology of the mother lode in the area. MacBoyle would not allow it, possibly to not give away any of his successful secrets. The mine complex was tunneled down to almost 3,500 feet.

Under MacBoyle’s guidance the Idaho-Maryland Mines produced a collective total of $40 million over the years. His prominence in the mining community grew and he became chairman of the California state mining board in the early 40s.

It all came to a halt with War Production Board Limitation Order L-208, issued on Oct. 8, 1942, which forced the closing of the mines not only in the area, but the entire country. The lack of available manpower was hindering operations anyway. The company did keep a minimum number of employees to keep the pumps running. By the end of 43 though the mines were showing signs of neglect. After the war operations limped on, even switching to extraction of tungsten, but it all ended in 1957 when the operation was liquidated. Without MacBoyle's keen sense of how to find profitable gold to extract, plus other economic factors we will see shortly, MacBoyles gold mine of a gold mine was not any longer. In 1963 the land, and mineral rights were sold for just $52,500.

MacBolye's homestead - "Loma Rica"

MacBoyle also had an interest in horses, and in 1934 he bought land from the Idaho Maryland Mine, just northeast of his mines to breed and train Percheron draft horses and Thoroughbreds. He also had 220 acres of orchards. The Loma Rica Ranch, as it was called, was once the largest thoroughbred horse ranch in the state. MacBoyle built a $50,000 redwood barn in the early 30s for this endeavor.

He had a fountain commissioned which was modeled after one displayed at the 1939 Golden State international exposition on treasure Island built on his property near the present-day airport. It still flows in a reservoir that was created to supply water to the ranch and the mines. The fountain was built using the actual electrical wiring, panels, and lights that were used in the original Fountain of Western Waters at the exposition. The fountain is at one end of the reservoir, and at the opposite end is a gazebo, which housed the control room and electrical wiring for the fountain and lake. He loved the site and had trees planted around the lake with the intention of building a house there.

On his ranch he gave jobs to those who needed it during the depression, whether he really needed the work done or not. There are eyewitness accounts of workers paid to move something, and when done told to move it again, or to fix or rebuild fences, etc., that did not need any attention. He employed more carpenters, stable and ranch hands than the ranch needed. During the Depression he generally hired anyone who was willing to work.

Besides creating jobs for the local unemployed, he supported the construction of a new St. Patrick's Catholic Church in town, across the street from the original. With the full support of the Department of Fish and Game Commission he made the mine and the ranch refuge for pheasants, quail, and partridges which he released into the hills. Errol MacBoyle was an avid sportsman and a strong conservationist.

Transportation

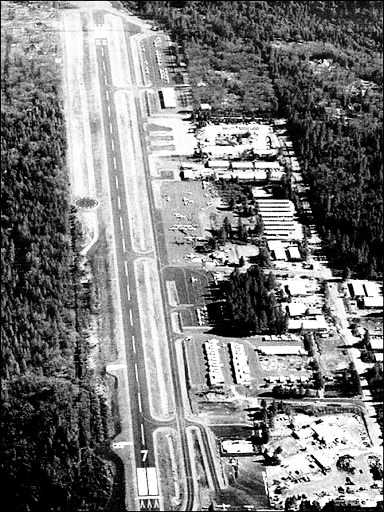

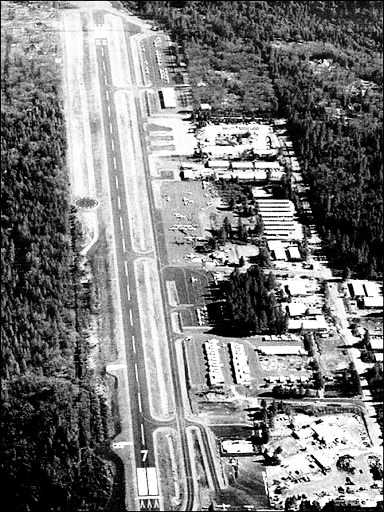

Loma Rica, now Nevada County Airport

MacBoyle built the Loma Rica airport in 1933 at the southern extreme of his ranch to fly gold to Mills Field, eventually becoming San Francisco International Airport, and from there ground transport to the San Francisco mint. Today the airport is known as the Nevada County Air Park.

Airport in more recent times

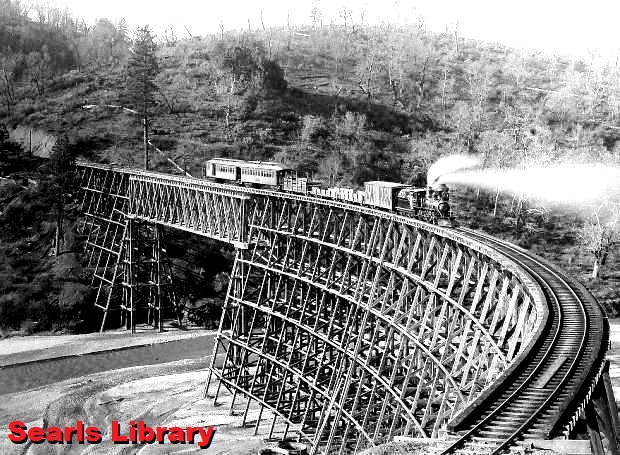

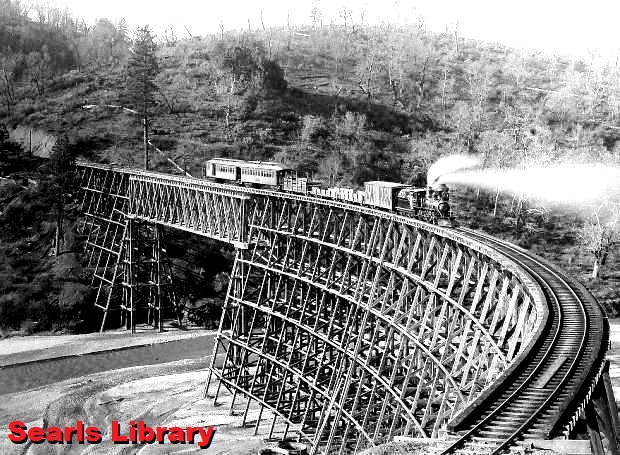

Up until then besides trucking the gold to San Francisco, the other way was via the Nevada County Narrow Gage Railroad (NCNG RR), that ran from 1876 through 1943. When the steel rail became worth more than the railroad itself, as steel was needed for the war effort and roads had improved enough that the rail route was no longer needed, the tracks were ripped up and the rail sold. The 23-mile line, which connected with the main Southern Pacific line in Colfax, ran up through Grass Valley to Nevada City. The path included two bridges, two tunnels, and five trestles. At one time the bridge over the Bear River was the highest in California, at 100 feet in height. The small railroad even hauled the circus up to the two towns occasionally. In 1893, as a circus train crept around a horseshoe curve the animals in one of the cars leaned against the side of the car on the outside curve, which tipped the car over and derailed most of the train with it killing two crew members. It hauled out $200 million in gold over its lifetime.

NCNG - 1895

The only artifact that might survive this railroad might also be on its way out in the next couple years. John Kidder was the chief engineer and builder of the railroad. Originally from New York, Kidder's career included stints in Nevada, several places in Northern California, serving in the California State Legislator for two years starting in 1865, along with Oregon, and Washington states. He became the leading engineer for building the Oregon and California railroad, and then the same on the first narrow gage in California, the Monterey, and Salinas Valley Railroad. In 1875 he settled in Grass Valley when he oversaw the building of the railroad to town.

John Kidder

Kidder was the first, or charter president of the Grass Valley Elks Lodge in 1900. Somehow, he managed to include a bunch of box car leaf springs into an auditorium in the lodge. They were incorporated to give its floor bounce. The floor is currently one of the few "bouncy dance floors" left in the country. Although the building is historic, being built at a time when Elk Lodges often were more than just meeting places, but an integral part of the community, it still has apartments, and even a coffin closet in the main meeting chamber for memorial services, and a currently non-functioning bowling alley, its sits prominently on Main Street, making the property valuable, and the building possibly replaceable.

Sarah Kidder

Another footnote to this story is that right after Kidder headed up the lodge he passed due to complications from diabetes, and before he died he signed over three-quarters of the railroad's stock to his wife, Sarah Kidder, as he had come to take over and become president of the railroad and had reached multimillionaire status by 1884. She was voted in as the president of the railroad, the first female of a railroad ever. The 12 years she was president were known as the "Golden Years" as the railroad at this time was at its most peak in earnings. She sold out in 1913 and retired to San Francisco. Their mansion, next to the Grass Valley train station, hosted governors, senators, and one frequent visitor, Mark Twain. Before her husband’s death she led the towns socialite scene as possibly the richest woman in town, but after her husband's death discovered her business acumen. After she left town the house fell into disrepair. In 1940 a tank car full of asphalt caught fire at the depot, and extensively damaged the train and the nearby mansion. The railroad had stopped carrying passengers the year before. Today all that remains of the two structures are parts of the building’s foundation, and a retaining wall on Bennett Street. That street is named after the last superintendent of the nearby Empire Mine.

Gold mining affected the building of the railroad main line through Colfax in the 1860s. The Southern Pacific mainline was originally the Central Pacific Railroad, construction began on the transcontinental rail line across the Sierra Nevada in 1866, but jobs on the railroad construction teams were not lucrative enough to lure workers from the mines. The problem the railroad had was the opposite. In one celebrated case, 95% of a 2000-man construction crew fled for the Nevada County mines almost as soon as they arrived at the end of the track and had been fed a warm meal. Chinese laborers largely took up the slack to get the railroad over the rest of the Sierra. When the railroad was completed in 1869 one affect was to transform the cultural and economic landscape of the Sierra Nevada from an isolated frontier dominated by independent placer miners to agrarian communities of families who more diversified the economy and now had access to outside markets.

Hospital

Never completed as a hospital, but ended up being the genesis of all the high tech that followed

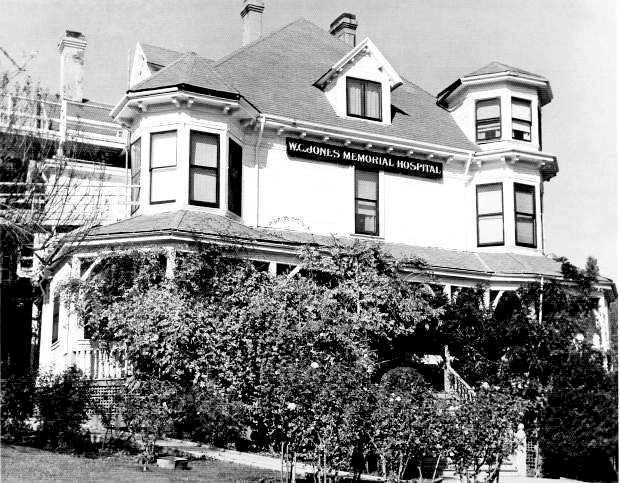

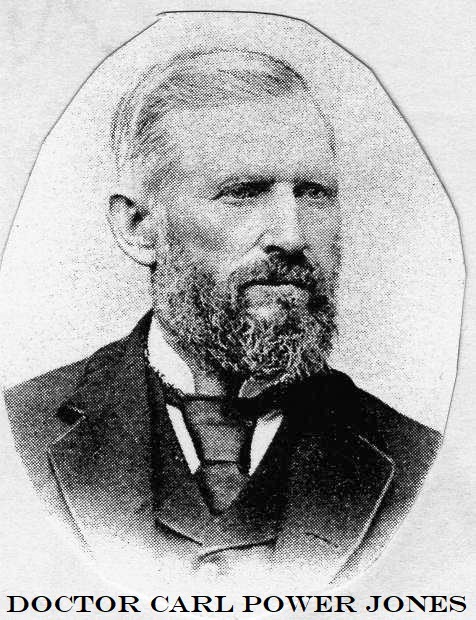

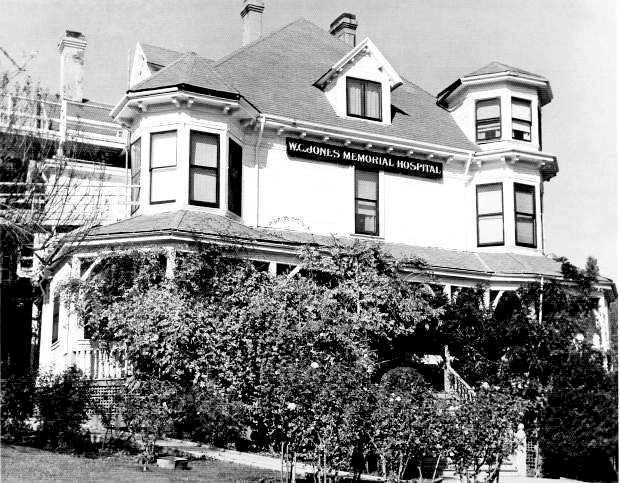

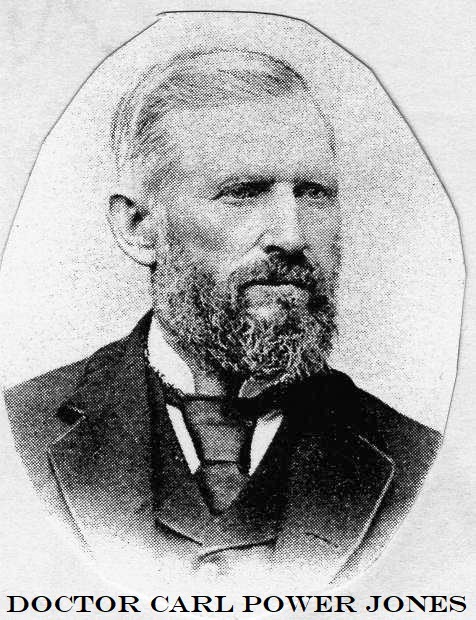

Perhaps the most profound contribution MacBoyle made to the area was a hospital that was never completed. With the help of his friend, Doctor Carl Power Jones, Errol MacBoyle conceived of building a new hospital for the Grass Valley area. They formed the Grass Valley Memorial Hospital Corp. Dr. Jones had a brother who was instrumental in founding one of the existing hospitals as a memorial to his father, Dr. W.C. Jones, a prominent local doctor, and surgeon. It opened in 1907. The hospital was housed in what was really a large residence, in a residential neighborhood a little south of the center of town. Originally built in 1867 by the Fahey's, owners of the Allison Ranch Mine, the property was later sold in the 1870s to a prominent financial tycoon and investor, William Campbell. After the building was later sold in 1906 to Dr. John Taylor Jones, Carl's brother, Nevada County's first private hospital was founded. That building today is a bed and breakfast.

The area was in dire need of a more modern hospital. At the time there was the Jones Hospital and the Nevada County General Hospital built in 1860, and slowly expanded over the years. A problem was that it was at the extreme east end of Nevada City with most of the population all west of it. The two men wanted to build a modern one more in the center of the two towns, not far from where the current hospital for the area is located.

Being built in 1939

MacBoyle donated over $400,000 for the Grass Valley Memorial Hospital which was to be built at the location on what is now known as Litton Street. Local lore says Errol MacBoyle and Doctor Jones played cards and planned the new Grass Valley Hospital in the gazebo across from his fountain. Neither Doctor Jones nor Errol MacBoyle would live to see their dream completed.

World War II not only stopped the mines, but it also stopped construction of the hospital. While the outer shell was completed the interior was not completed for another 15 years due to a shortage of steel, cement, and other materials due to the war effort. The current hospital, not too far from the MacBoyle's would be one, opened in 1958. Dr. Jones was a founding member of the group that eventually built Sierra Nevada Memorial Hospital, did not opened its doors until December 1958.

On October 23, 1943, Errol MacBoyle suffered a stroke which left him an invalid and requiring constant medical care and supervision. At this time, his wife spent some time in the area to help look after him. On November 4, 1949, Errol MacBoyle died at his Loma Rica residence and was buried in Grass Valley at the New Elm Ridge Cemetery. The MacBoyles were childless. After Errol MacBoyle's death, his wife, Gwendolyn remarried, but was interred next to Error when she died in 1962. MacBoyle's last known next of kin, a cousin, died in Laguna Beach, California in the 80s.

Which the exception of a short dead-end street a little south of where his ranch was, little in the area bears his name today. The 452-acre ranch sold for $7 million in 2002. Currently the part of the ranch west of Brunswick Road, are open for possible development, although the stables on the other side of the road appear safe.

Even though, his legacy lives on, not through his name, but through an airport, and more importantly as we will see, through his failed hospital.

The End of an Era

Rotting timber; what happens when mine shafts are not maintained

The great depression, 1929 to 1941, ushered in the last hurrah in large scale gold mining in the area. The 1929 stock market crash resulted in the ensuing run on banks, as well as people hoarding gold, which threatened the US treasury's solvency. Consequently, federal policy during the early 1930s was designed to encourage the return of gold coins, especially to the ailing banking system. President Roosevelt signed an executive order in 1933 requiring the return of gold to banks in exchange for non-gold currency. The order fixed the price of an ounce of gold from $20.67 to $35. An ounce of gold was valued at $20.67 up until then, as a $20 gold coin was minted with just under an ounce of the metal, thereby overvaluing gold and undervaluing the dollar note, but the order prevented future market adjustments for inflation.

This new valuation immediately made the mining of gold much more lucrative. The problem is that price remained the same until 1971 when President Nixon abandoned the gold standard. So, after the war as costs rose, the return for gold did not. Back in the 30s the increased gold value provided a viable alternative for the unemployed, who took up traditional placer mining techniques again, providing a boom of another kind to the local economy. Statewide in the mid-30s gold production rose above the million-ounce threshold for the first time since the 1915-1916 depression, and the extended booms of early statehood. This incredible resurgence lasted 6 years, from 1936 until 1941, with the second all-time high for US gold production rates in 1940.

But World War II upended this dynamic. The area employed about 4000 in the mining industry when the war struck. After the war, many of the miners did not come back to their previous jobs. Many had new skills and professions thanks to their military training. Some went to school using the G.I. Bill, or Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944. The miners that came back and were experienced in the trade were generally an aging workforce. This all contributed to a general shortage of productive miners, which resulted in not being able to work some of the more difficult, generally in the lower levels of the mines, where the richest deposits were. Even though the Empire Mine kept about 175 men on the payroll for the three years the mines were closed during the war, many of the mines needed extensive repair, and the cash flow was no longer there to keep them up. The expertise in maintaining the extensive pumping system to keep the mines de-watered was dwindling. Many of the lower reaches of the mines where slowly filling up with water.

Partially because of the shortage of labor, wages were forced up, and with the price of gold still pegged at $35 oz, many veins were no longer viable money makers. The Empire-North Star mine attempted to revive production in 1947 by leasing blocks to about 125 miners and providing all the support, such as blasting powder, as well as employing about 200 men to support the mills and other infrastructure. They also offered their mill to process orders for neighboring mines. But they still operated at a loss. In 1956 miners walked out, striking for better wages, but the mines didn't have the money to raise wages, so in January 1957, with the strike still on, the Empire complex began to liquidate their assets, allowed the workings to flood, and closed the mine by summer, the same year the Idaho-Maryland Mine shut down.

During the mine's final downfall, Ellsworth Bennett, a 1910 graduate of the Mackie School of Mines in Reno was the last Superintendent of the Empire. His age was also indicative of the aging expertise the industry had at the time. He was the only person from management allowed across the picket line during that last strike as the miner's knew their lives depended on his engineering skills to keep the mine safe if they had returned from the strike. Bennett oversaw the closing of the Empire on May 28, 1957, when the last Cornish water pumps were shut down and removed. In its final year of operation in 1956, the Empire Mine had reached an incline depth of 11,007 ft (3,355 m).

Most deep mines, if not continually pumped free of water, will eventually fill up

In 1958 the entire holdings were sold at public auction. It took until December 1961 for the last vestiges of the company to be wound down, and the final staff to clear out. The main head frame to the Empire Mine was determined a safety hazard in 1969, so it was raised by dynamite. A company briefly acquired 770 acres of the Empire's holdings in 1974 for $1.43 million, excluding the mineral rights below 100 feet in some places, 250 feet and others. That same year the land was bought by the state for $1.25 million and developed into the Empire Mine State Historic Park. Today the park has 853 acres of land. The Newmont Mining Company retained the mineral rights to the Empire Mine, and 47 acres, which left the option of re-opening the mine in the future.

Since the 70s the price of gold has definitely trended upward to a point where it is not uncommon for it to be over 50 times what it was in 71, interest in reopening the mines is almost always being discussed, usually with very fierce local opposition. Local opinion often follows the argument that it is not fair to people who have purchased homes near the mines with an understanding that mining was done. In addition it is claimed by locals that the outside business entities that are proposing reopening some mines have no vested interest in the community and will operate the mine as long as it is profitable and will abandon the community when there is no more money to be made. In addition, critics worry that the local community will be left to deal with any collateral damage that may occur.

They recall the 1996 San Juan Ridge calamity, the site of the "Malakoff Diggins" mentioned in the last chapter that caused so much environmental damage 150 years ago. It was reactivated for a while until it breached an aquifer and drained the wells of a dozen private residences, along with the well of the local school.

The mine that is under consideration

The ground water argument carries over to the fact that the mine most often talked about reopening, the Brunswick section of the Idaho-Maryland complex, is claimed that it would need to pump up to 3.5 million gallons of water out of the ground daily, which is claimed to be nearly one-third of the total daily groundwater use in all of Nevada County, impacting the underground aquifer which provides water to hundreds of families, businesses, and family-owned farms. Besides pumping the water out of the flooded tunnels, the water would have to be treated to remove any toxic materials, and then discharging it into Wolf Creek. Discharge rates discussed run as high as 2,500 gallons per minute, a flow roughly equivalent to flood stage for the creek, until the mine is drained. It is claimed that after the initial de-watering, ongoing de-watering would send about 850 gallons per minute into Wolf Creek to keep the mine from refilling with water.

Just as big of an issue would be what to do with all the tailings extracted. Some proposals have included the generation of 1500 tons of ore a day would be produced, out of which only a few ounces of gold would be recovered. A reason that gold is so precious is that even though it can be found almost everywhere, it is so diluted that even in rich veins there is the exceeding small fraction in weight of the precious metal, about one millionth of the material extracted is actual gold.

Needless to say, hard rock mining on any noticeable scale is almost certainly in the area's past. The state of California has also made it awfully hard for individuals to placer mine in local streams. Limiting the tools to what is essentially garden trolls, and not allowing more than 50 pounds of material to be carried off site for panning somewhere else. Many hobbyists like to pan material where they are not in cold running water, but in their garage, basement, or even the kitchen table. The result today is that there is not much measurable economic activity in the area that is based on the extraction of gold.

It should be mentioned that there was another industry that ran parallel to mining, and that was logging. Early on wood was the chief building material for mining equipment such as the long tom, sluice box and large flumes for channeling moving water. When placer mining had played out and as hydraulic mining was being curtailed, underground hard rock mining expanded. The demand for timber grew rapidly and the lumber industry took off in the area. All needed timber to shore up tunnels, wood to run early steam boilers, which powered mine equipment and pumps. Also, as mining grew, at one time the area had about 95 mines, the surrounding communities grew also, and with almost constant fires, constant rebuilding required wood.

Early on planks of lumber were made by hand sawing timbers with whipsaws. Man-powered sawmills were common in mining camps. Demand for large scale timber to support underground work grew rapidly, and as nearby lumber was exhausted sawmills sprang up further from camps and towns higher into the mountains following the receding timber harvesting sites. Soon to keep up with demand waterwheels were installed to power sawmills. Soon steam powered mills were added to the mix. The area lumber industry often fluctuated economically with the mines, but as the railroad reached the area and it needed tens of thousands of wooden ties alone, distant markets opened, such as providing wood for the silver booms in Nevada, and construction material for growing west coast cities, especially San Francisco, and the bay area. Closer to home Sacramento was another large market for the mills. As roads and trucks improved getting product to market became easier.

But the area never had more than a half dozen sawmills of any size, and although gold mining made logging a viable business in the area, it never rivaled mining in scope and heft.